This article is also available in Spanish, translated by Gerardo Gacharná Ramírez.

First of all, let me clarify. This article is NOT going to be about copyright. While it may be a valid reason (or even the least debatable reason) as to why to ask for permission, I'll give you a very non-legal opinion that will hopefully convince you by itself - irrespective of what the law may say or not.

Why ask for permission?

Put concisely, my motivation for asking for permission is based on ethics, rather than laws. Hopefully this section will capture that motivation more extensively.

Making videos is a great way to share origami designs. Just like diagrams and crease patterns they make models more accessible. Especially when these methods of documenting models are shared, asking for permission to do so before is the right thing to do. Well, that's my opinion. But maybe you disagree. That's why I want to give some insight into why I have my opinion.

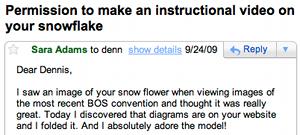

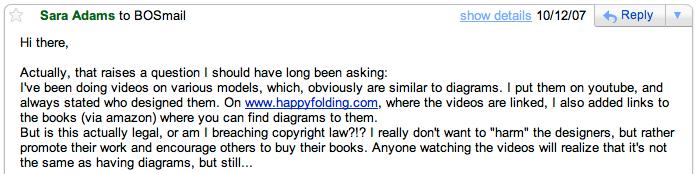

It is probably more common practice to ask for permission for more traditional ways of sharing. For example, would you ask for permission before making diagrams? If they're for personal use only, many of you may negate that. So let's say you do want to share. If you want to make them accessible online, you may still not have a clear opinion (although I'd hope more of you affirm this). But what if you want to publish them in a book? Would you contact the designer to inform them and get an ok? I hope at this point you'd answer with a "Yes." But what's the difference between publishing content in a book and online? I guarantee you, your potential audience isn't smaller. The image on the right shows that the video of Dennis Walker's snowflake, which I uploaded a year ago, already has 388,290 views (as of January 17th 2011). That should be proof enough.

I think these three different cases - personal use, online availability, and publishing in a book - show that everyone has a line they draw between having to ask for permission or not. And my point is, if you did draw a line somewhere in those bounds, then you'll have already agreed that asking for permission to make video diagrams is necessary. In essence, the effect is no different than publishing in a book: with videos you make the model accessible to others out there, just like it's done with diagrams. And again, your potential audience can be greater than that of books, so asking for permission should be on the top of your list.

But why ask for permission at all? If you ask yourself that question, I'd like to suggest an exercise: try to design something. This is something I'd encourage everyone to do, by the way. (On the left is a picture of the result of such an exercise I did.) It can be a superb experience. But in this case it may also show you that there's a lot of work and thought and - yes - love that's put into the creation process. Now usually when I make a video the designer hasn't just designed something wonderful, but also diagrammed the model. Diagramming not only includes actually drawing the step-by-step instructions, but also working out a nice folding sequence. The designer will also probably have changed the design to make it more accessible, to clean up some inside layers, or to offer a nice variation.

Why am I saying all of this? To make clear that designing and diagramming a model is a huge effort. I respect that work a lot. And as an origami enthusiast, you probably do, too. But having respect also means we should show that respect. And what better way to show your respect than by contacting the designer if you want to do something more with the model than "just" fold it? This applies to various other means. For example, you may want to teach the model at a convention or sell some folded models for a good cause. In all cases contacting the designer and asking whether this is ok is what you should do. Not only does this show the respect for the designer's art that it deserves, but it probably also puts a big smile on his or her face. What better flattery for a model is there to love it so much that you want to share it with others?

How to Ask for Permission

Finding the Contact Details

Finding a designer's contact details can be as easy as finding their website. For example, you may want to enter the designer's full name and "origami" into your favorite search engine. If the designer has a website, chances are it's going to be one of the top results. Websites will usually include contact information. This may either be an email address or a contact form. In some cases it may also include a postal address - although this is rather unusual.

If a designer does not have a website of their own, they may still be online. Then you may want to check whether they are members of a community platform you are also a member of (e.g. Flickr or Facebook). You can also send a message to an origami mailing list (for example the O-list). You may be lucky and a reader has the designer's contact details, or the designer is on the list themselves.

Side note: You should never pass on contact details without the designer's permission. If I am asked for contact details, I will always suggest the person sends me the message, and I can then forward it to the designer. The designer can then choose to answer and expose their contact details. In essence, it is the designer's decision whether someone else should have their contact details.

Another resource are origami societies. If you know which origami society a designer is a member of, you can contact them. The society may be able to give you the contact details, or agree to pass on a message. Usually, designers will specify whether contact details may be passed on to others, or the society will ask them whether they are ok with it in that instance. Note that most societies will restrict this service to members only.

But what if you don't know which society to contact? In that case it's a good idea to contact the origami society of the designer's home country, and maybe one of the bigger origami societies (such as Origami USA!).

Finally, you may sometimes be lucky and actually meet the designer at a convention. Then you can talk to them about your project directly, or ask them for their contact details. I personally prefer sending a message, rather than asking in person. The reason is that I do not want to pressure the designers too much to give an answer directly, or indeed at all. I believe a good compromise is to explain your project and give the designer your contact details. You can also offer to send them more details if they give you their contact details. By stressing that you do not want an answer right then and there (or indeed during the convention), but only after they've had time to think about it some of the pressure to answer can be reduced. Another aspect of letting the designers give their answer in writing is that both of you then some kind of documentation that permission was given. It's much better to have this in writing, than to trust in your and their memory.

Writing the Message

First remember that you are contacting the designer and asking them for something. So do put some time and thought into writing your first letter. You will want to explain what you are asking permission for. In the case of videos, some questions you may want to answer in your letter are:

- How will you publish the videos? For example, will the videos be posted online and on which platform? Or do you want to put them on a DVD? Do you plan to sell that DVD?

- Will viewers be able to access the video free of charge, or will they be charged? Are you planning to compensate the designer, and how?

- How will the designer be credited? What do example videos you produce look like?

In my messages I answer all of the above questions, and a couple more. For example, I also tell them about how my video project came to be and what my motivation is. I usually comment on why I want to demonstrate a particular model and what I especially like about it. And I always make it crystal clear that if they do not reply, or do not want me to do a video, I fully respect that. This is an important point, actually.

Dealing with Negative Answers

When asking for permission you should always be clear about the fact that the designer may say no. Asking for permission only makes sense if a negative answer is respected, i.e. you will act accordingly. The same holds if you do not get an answer back. The designer may be happy for you to do a video, but you do not know. Has this happened to me before? Yes, definitely. I've had designers decline my request of making an instructional video, and I've had some of my messages unanswered. In the latter case, it's likely that at least some designers did not get my message, because I used a wrong or outdated address.

While I am always sad about negative or missing answers, I have gotten a lot of positive answers back. Indeed, I've made the experience that many designers are happy to share via this new medium. There are so many that approve that I have more models I'm allowed to present that I can fit in my time. That means that if you get a negative answer - rather than disrespecting the wish - you should try contacting a designer that approves your request of making a video.

Language Barriers

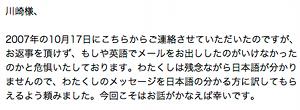

You should be aware that not all designers are fluent in English. In some cases it may be a good idea to translate the message into their language. When contacting Toshikazu Kawasaki, for example, I had an Japanese friend of mine translate my letters. While Toshikazu Kawasaki had not answered my first, English letter, he did answer the ones that I sent in Japanese. The picture on the left shows a small excerpt from that translated message.

When translating messages you should take care that the translation is of a decent quality. You may also ask the translator to attach a notice that the text was translated, and attach the English version of the text.

Is this too much of an effort? Always remember that you are asking the designer for something, not the other way around. So you should try to make it easier for them to understand that request. This starts with using correct grammar, punctuation, and may end with getting the message translated into the designer's native language. This may seem like a big effort, but in comparison to designing a model I believe you still have the better deal.

Some Designers that have given me Permission

I will not post a full list here, but a relatively complete list is on my website. I will say that some of the first designers to give me permission included Dave Brill, Carmen Sprung, Robert Lang, and John Montroll. This is just to say that even at the start of my project very well-known designers supported my project. I am very grateful for that.

Getting a Wrong Start

Maybe you've already made videos without permission. Or published diagrams, or taught at conventions, or sold origami. Maybe you had a wrong start. Do I condemn you for that? No.

Not everyone may know that I did not ask for permission to make my videos right from the start. It was not ill will, but in some ways thoughtlessness. I hadn't thought I needed permission. Note that back then I wasn't really part of the origami community yet, and was a bit unaware of all the goodness going on there. But then I did join an origami mailing list and introduced myself. I mentioned that I made origami videos. Dave Brill contacted me, saying that he'd seen I'd posted videos on his models, too. While he said he was ok with this, he'd ask me to tell him about any future plans I had on presenting more models. I was dumbfounded. I started thinking about what I'd been doing. And felt extremely guilty. I made a decision. From now on I'd ask for permission before posting any video. I also decided to ask for permission for all the videos I had already made. I decided that if I didn't get a response within two months, I'd take the video offline. Or if I got a negative answer to remove them right away.

I am happy I took that path. Yes, some videos I made aren't available anymore, because the designer didn't give me permission, or because I failed to find contact details for them. But, oh, what did I win! Not only do I believe asking for permission is the right thing to do, it's also great to be in touch with designers. Some are very appreciative of my work, and some I have continuous correspondences with. When I am lucky enough to meet them at a convention, I can get to know them better, and thank them again in person. Rather than them being names in a book full of wonderful models, they have become real people. I guess this sounds strange, but that is something I in some ways did not realize in the beginning. Behind every model there's a designer that created it, and put some part of themselves into that model. Behind every model there's a person that deserves to be respected. Behind every model there's a great person to get to know.

So, if you had a wrong start, too, that's ok. But it's important you change that path, just like I did when I realized - with the help of Dave's message - that I was wrong. Maybe this article is your point of realizing. And your point of change. It's definitely worth it, you may be surprised how gratifying it is to not only know you're doing the right thing, but also to see the effects, and get to know lots of wonderful people on the way.

But What about Copyright?

So you do want to know what the copyright situation is like, and what my thoughts are?

Personally, I have decided to ask for permission, because it is the morally right thing to do. In that I don't care all that much whether law also requires me to do it. Do I think it should be required? Yes. And that's all I'll say on that topic.

Now if you want to read more on what the copyright is like for origami, you'll probably not find a definitive answer for every country. But you may find the following pages interesting, and they should give you a good start: